I remember where I was on September 11, 2001.

Sitting on a park bench in a London suburb enjoying a quiet day off. An elderly couple nearby were exchanging greetings with a park gardener. I wasn’t eavesdropping, but did overhear one phrase being repeated: “We’re lucky here. Look at other countries on TV, they have buildings falling down.” Until I got home, I thought they were talking metaphorically.

I am not as certain of the exact location where I first heard about the Srebrenica massacre. The atrocity which saw units of the Serb supremacist militia of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of Ratko Mladić and political control of Radovan Karadžić, massacre over 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys whom they had separated from a larger group of civilians, took several days of reporting for its scale to become clear.

I do know that I was sat in a small hall full of Bosnian people in London. But exactly which venue and day in July 1995 eludes me. As does why and how an old family friend had come along. After three years of the most destructive conflict in Europe since WWII, which saw over 100,000 people killed and half of Bosnia’s population displaced, the news from Srebrenica, a supposed “safe haven” overlooked by UN troops was a new low.

What I remember most is the solidarity in the room as a panel featuring Vanessa Redgrave read out harrowing details from some of the earliest reports of the atrocity. At the end, despite being given many reasons to feel upset or angry, the room, as one, silently composed itself to give the Bosnian ambassador a deeply dignified ovation.

Moving as it was, the day soon sank into the depths of my memory, filed under “meetings I have attended.” That is, until a recent pandemic-induced bout of documentary viewing.

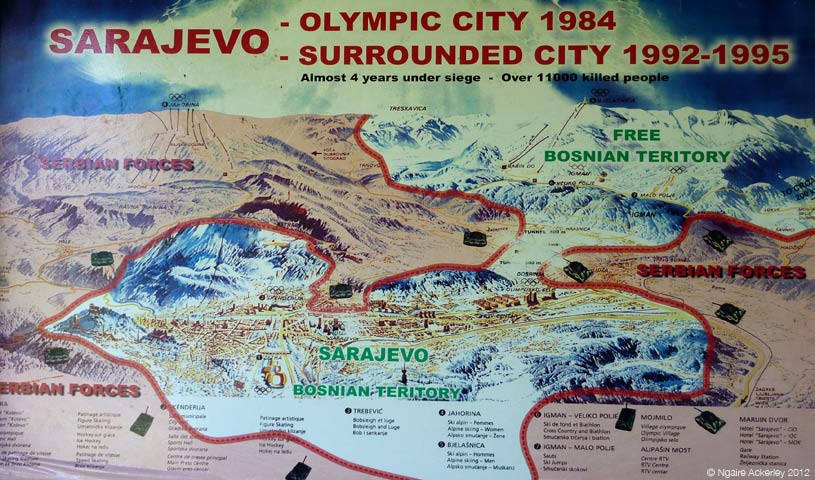

Scream For Me Sarajevo, a 2018 film by Tarik Hodzic tells the unlikely tale of a concert by Bruce Dickinson, lead singer of the British band Iron Maiden, in the Bosnian capital in December 1994. This was during the 1992-96 siege of Sarajevo (longer than Leningrad), which saw the host city of the 1984 Winter Olympics surrounded by heavily armed militia bent on reducing it to rubble and murdering civilians at will.

The contrast between the theatrical legend and heavy metal frontman, (who each I am sure vote differently,) was big enough to prompt my memories of Redgrave’s speech to return.

Why, besides not being a fan, had I not heard about Bruce Dickinson’s Sarajevo concert before? I bought War Child’s Help album and the U2/Pavarotti Miss Sarajevo single in 1995. I had a Workers Aid for Bosnia t-shirt and knew U2 used satellite link-ups during a world tour to speak to besieged Sarajevo residents, but did not play Sarajevo before 1997.

I assume the music press was lukewarm because he had become a solo act at the time. But it also seems Dickinson did not talk about it much until two decades later after Bosnians who attended the concert as youngsters had begun filming their recollections, and his band was invited back for a return visit and civic honour.

The film makes clear his uncharacteristic reticence. The experience itself was enough. Despite being told to return to the UK after it became unsafe to fly into Sarajevo, Dickinson and his fellow musicians on the spot decided to hitch a hair-raising ride through the war zone with The Serious Road Trip, a volunteer aid convoy known for its bright yellow trucks.

A choice as foolhardy and brave as it sounds. This journey alone makes every tale of rock star excess and smashing up hotel rooms on tour, redundant and trivial. It is heartening to see a documentary record it because though small, the 1994 gig is truly inspirational.

Bosnia still bears the scars of ethnic cleansing. But Mladić and Karadžić have been duly convicted of genocide for Srebrenica by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Slobodan Milošević, the Serbian president who had armed them using his control of the former federal republic’s armouries, died whilst on trial for various war crimes. Bosnia, Serbia, and Kosovo are now at peace and seeking EU membership.

Apologists for the Milošević regime (of whom the UK had plenty across the political spectrum,) will never admit it, but if the Bosnian government in Sarajevo had not been hampered by a one-sided arms embargo, it could have ended the siege years earlier. The fascist VRS only had a head start in weapons, not in allegiances of most of Bosnia’s people.

I remember standing in a different, larger London park on February 15, 2003. It is possible that regret at the slow response to aggression in the 1990s helped turn Tony Blair into a rampant interventionist unable to tell the difference between a just liberation war and one that risks doing more harm than good.

For what it is worth, I could still tell. As did the over a million other people marching into Hyde Park that icy day to protest the imminent invasion of Iraq.

Sarajevo was worth supporting. A beacon of light during the wars that afflicted post-communist Yugoslavia as it disintegrated amid a tide of hyperinflation and toxic ideology.

Sarajevo’s residents did not turn against each other. Muslim, Catholic, Orthodox, Bosniak, Croat, Serb, or mixed, they stayed united as Bosnian citizens. For the most part, its people ate, drank, suffered, and looked the same anyway. Not that this would have mattered to the paramilitaries who had brought back concentration camps to the heart of Europe.

If you are thinking Scream For Me Sarajevo might be depressing, it is actually the opposite. A highly watchable and uplifting documentary. Nobody pretends to be neutral. The performers and UN personnel do not shy away from showing their empathy and shell shock at what Sarajevo’s residents had to endure. For their part, the teenage fans turned 40somethings do not talk about wanting to fight during the war, they talk about wanting to survive and enjoy themselves and of how music inspired the dreams they have followed.

As of this month, I have not been on a plane for four and a half years, to be extended no doubt by the pandemic. I am so accustomed to this that I have stopped imagining flying anywhere new again, only familiar places and family.

This documentary is so life affirming, at least for me, I can now at least consider the possibility of maybe one day making an exception. For Sarajevo.

published in Dhaka Tribune op-ed 24 January 2020

Once upon a time in dystopia (3 April 2024)

About 16 months ago, a vague sense of intuition prompted me to swap a lazy Saturday for a day in hospital where a scan was to reveal two strokes, both old but hitherto unnoticed.

Given my family history, they were scarcely a surprise, but still made the weekend more interesting. Over a year later, I can say that, aside from two sleep-interrupted nights searching for symptoms, I quickly got used to the extra medication and check-ups, for which I am grateful.

Life is for living — carry on, at least while you can. As soon as we become aware of our own frailty, our core instinct is to delay the inevitable, even if one believes in a better beyond.

Family, faith, friendship, and living a good life can all provide comfort, but to the cynical are mere distractions from the fact death has been stalking us since our first breath. It is human nature to look on the bright side of life, otherwise nobody would live next door to a volcano.

Sometimes it is a matter of survival and normality to turn a blind eye to the bad stuff. And sometimes, the bad stuff is you.

The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s film about Rudolf Höss the commandant of Auschwitz during WWII, portrays SS officers bureaucratically orchestrating the mass murder of Jews, Roma, and other civilians. As the film largely limits on screen atrocities to black smoke billowing out on the other side of the fence while Höss and his wife bring up their children and plant a pleasing garden, it is profoundly disturbing.

Like others, I was most shocked by the casual way Mrs Höss distributed coats and jewellery looted from murdered Jews among friends at a coffee morning. This might not just be about some evil Nazis; it could be about any of us today as consumers. We might not live next door to an exploitative sweatshop in the supply chain of shops we buy from, or a dangerous mine supplying minerals for our computers and phones, but we probably know or can easily learn that such things exist.

We may not be enthusiastic participants but can still be seen as benefiting from systems that perpetrate misery on fellow human beings. Is saying so dubious moral equivalence, a step too far in self-flagellation, or just another example of how humans tend to look the other way?

In his much-debated Oscar acceptance speech last month, Jonathan Glazer expressly drew attention to the victims of the ongoing attack on Gaza and the part played by dehumanisation in escalating suffering, prompting his parting question: “How can we resist?”

People prefer dystopias in films to seem far-off, fictional, and preventable

His comments on the war deservedly earned praise (as well as predictable wrath) but he also made clear his intentions in making the film, were to be timeless, not topical: “All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present — not to say, ‘Look what they did then,’ rather, ‘Look what we do now.’”

For the most part, people prefer dystopias in films to seem far-off, fictional, and preventable. If a UK government started behaving in the authoritarian manner of the right-wing dictatorships founded on bombastic nationalism and scape-goating of minorities and refugees featured in the Hollywood versions of V for Vendetta and Children of Men, they would be stopped right? Ok, perhaps I should get back to you on this after the next election. It might not just be PM Sunak’s government on an accelerating downward spiral.

Whilst Alfonso Cuarón’s take on Children of Men is praised for seeming prescience, one reason its visuals pack a punch is many of its scenes are drawn from real life and contemporary events, like jets attacking a refugee camp, a Pink Floyd album cover, and prisoners being tortured at Abu Ghraib.

Strong actors, upbeat music, and familiar tropes from quiz shows and police procedurals are what most people prefer to recall about Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire, not the utterly heartbreaking lives its lead characters — and more importantly their many real-life counterparts — were trying to get away from. Escapism is what sells, even after screenwriter Simon Beaufoy added more politics and violence to Vikas Swarup’s Q and A by making the lead a Muslim member of an underclass hurt by communal violence and gangsters in Mumbai, instead of an orphan given a religiously neutral name.

Nothing less than we should expect from talented artists. Yet, when it comes to the ultimate matter of one’s own death, there are occasionally some religious people who prefer more to talk about end of the world prophecies. Non-believers are not immune from distraction either, with some cutting-edge physicists and science fiction writers alike wargaming ways in which the human species or its legacy can endure beyond the death of even galaxies.

Back on Earth of course, we are but finite flesh and bones. The instinct to try and improve life or at least hope, is what helps make us human.

If, like me, you find it faintly nauseating when someone privileged enough to be used to taking basic needs of safety, shelter, and sustenance for granted, inflicts their “gratitude journal” on others, consider this a warning. Although I don’t write one down myself, if I had to, then apart from family birthdays, the recent moments I would most recall would be a nerdy conversation about the etymology of a running joke with the writer of a hit streaming show which we both silently agreed not to prolong, and a handshake with Bernie Sanders.

The most surreal was unexpectedly finding myself asking Dame Lesley Lawson (aka Twiggy) about The Blues Brothers at the same time as asking the comedian Ben Elton how the world of today compares with the dystopian world of his 1989 novel Stark. That entertainingly featured a ragtag group of activists chancing upon a conspiracy by the world’s super rich to colonize the Moon to escape the imminent collapse of Earth’s food systems, brought about by their own greed.

Mercifully, they answered, with Elton true to form, also waxing lyrically about the sheer opulence and comic vanity of today’s overlords. Silicon Valley billionaires may be taken as Masters of the Universe but are anything but in the face of the cosmos and a good sense of humour.

Dystopias can always be overcome. Until the next one.

While utopia literally means “not a place,” and cannot exist, dystopia like death is always among us. We just prefer not to dwell on it.

https://www.dhakatribune.com/opinion/op-ed/343314/once-upon-a-time-in-dystopia